American students lag on international test

November 13, 2014

Up until this school year, junior Eleanor St. George, foreign exchange student, would settle down for her first class of the day at her private school in Australia at 8:30 a.m. Fifty-five minutes and one class later, she relaxes during a 20 minute recess. Two more classes and then it’s time for a 35 minute lunch break. She attends three more afternoon classes before dismissal at 3:30 p.m.

“[In Australia] there’s not many classes that you are required to take to graduate, but you have to take an English or literature class for all two years of your junior and your senior year,” St. George said. “And you must get an average C grade. And everything else is just whatever you want to do.”

St. George said the grading scale in Australia is very different from the one in the U.S. In Australia, a 50 to 70 percent in a class is considered earning a ‘C,’ a ‘B’ translates from having a 70 to 80 percent, and earning anything above 80 percent is acknowledged as an ‘A.’

“Overall I would say your science courses, AP science courses, are maybe a bit harder than we have at home,” St. George said. “But math, math is just different. It’s not that much harder. But things like your normal literature courses, AP literature courses, English and language arts, they’re similar if not a bit easier than back home.”

On the 2012 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) study–a triennial assessment of 510,000 15-year-old students from 65 economies—Australia, placing twentieth in math, thirteenth in reading, and sixteenth in science, outranked the US in all three subjects. American students came in at thirty-sixth in math, twenty-fourth in reading and twenty-eighth in science.

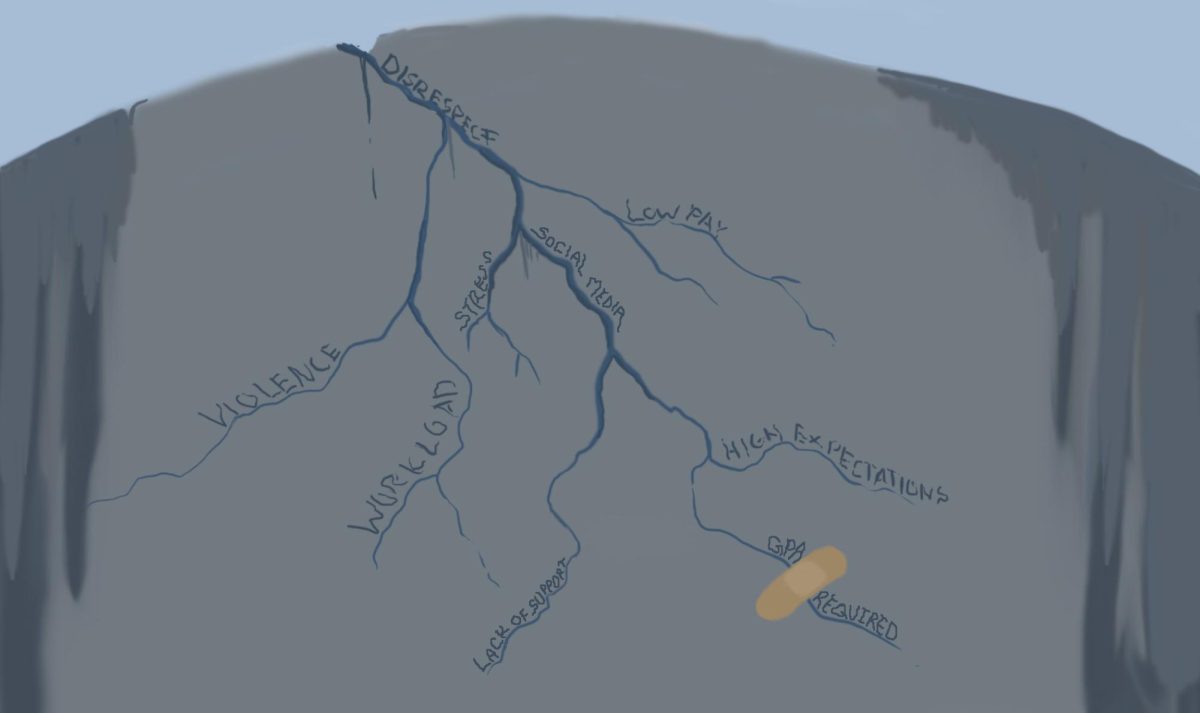

“The data speaks for itself on how our students compare with students from other countries on college preparatory exams,” Dr. Stuart Bunderson, associate dean and director of executive programs at Washington University, said. “And the answer is pretty clear that we don’t do as well. We’re not at the top; we’re quite a ways down. It’s not a matter of opinion. We don’t score as well.”

Although the US proves to fall behind many other post-industrial countries in terms of standardized testing for primary and secondary students, an important factor to keep in mind when evaluating the overall quality of the educational experience in the U.S. is higher education, Dr. Bunderson said.

“We have the best research universities in the world, and almost every country would recognize that,” Dr. Bunderson said. “And most every country aspires to send their best and smartest and brightest students to a U.S. research university for their college education, because they know this is where you go. So when you say the quality of education, we beat ourselves up and maybe rightly so.”

American schools don’t fall short across the board, Dr. Bunderson said. Usually, the schools that perform poorly do so very drastically. However, with schools that perform well, students are more competitive. Of course, he said, there is always room for improvement.

“We just have some school districts that are not adequately funded,” Dr. Bunderson said. “They don’t have good teachers, and they don’t have the norm of pushing our students as hard on subjects like science and math.”

Dr. Bunderson said a possible solution to improve education is to invest more money in under-funded districts and to acknowledge as a country that standards need to be higher.

To improve education, the U.S. government has implemented a variety of programs to improve students’ standardized test scores and college readiness, such as the Common Core—a set of math and English standards students should know by the end of each grade level—and No Child Left Behind.

“I am a fan on anything that we can do to attract good, quality teachers to public schools,” Dr. Bunderson said. “I think those are dollars very well spent, but for the programs themselves, you can argue about how well they’re being managed, and you can criticize the administration of some of those projects.”

Improving education in the US doesn’t have to solely rely on the actions of the school districts and the government. If a student is not excelling, most school districts offer a multitude of opportunities and options to become successful.

“Just look at Marquette,” Dr. Bunderson said. “You have classes that are honors and AP, so you can take those classes if you want. If you just want to do the minimum, you can do the minimum. It’s a question of if you want to push yourself.”

In this day and age, students have access to online resources like Khan Academy where they can learn as much as they want, Dr. Bunderson said. In most cases, if you’re motivated, there’s no excuse for not achieving as highly as they want to achieve.

“Now, that isn’t always the case,” Dr. Bunderson said. “There are those inner-city schools when resources are very, very thin and it could be harder. And therefore, we need to invest and do what we can to increase their opportunities, so for people who are really determined, they can find opportunities to really push themselves and prepare themselves for college.”

On the most recent PISA study in 2012, the top seven performing economies on the math section were all located in Asia: Shanghai-China coming in at number one, then Singapore, Hong Kong-China, Taiwan, Korea, Macau-China and Japan. Shanghai-China, Singapore and Hong-Kong China also earned the top three spots in reading and science.

Dr. Bunderson said many educators in Asia tend to hold students to higher expectations within their curriculum. They expect children to know more by certain ages, especially in science and math. However, he said he attributes academic success in many Asian countries not just to their school system and curriculum, but to their culture.

In Asia, many parents push their children very hard to excel academically, Dr. Bunderson said.

“It’s both the culture of the family and the culture and the expectations that are built into their curriculum that work together,” Dr. Bunderson said. “By the time they graduate from high school, they’ve simply mastered more material, and they’ve been pushed harder to push themselves harder to achieve more, particularly in science and math.”

Dr. Paul Peterson, director of the Program on Education Policy and Governance at Harvard University, said some countries give their students the option of attending a private or public school with the government funding schooling in both cases, which may attribute to their academic success.

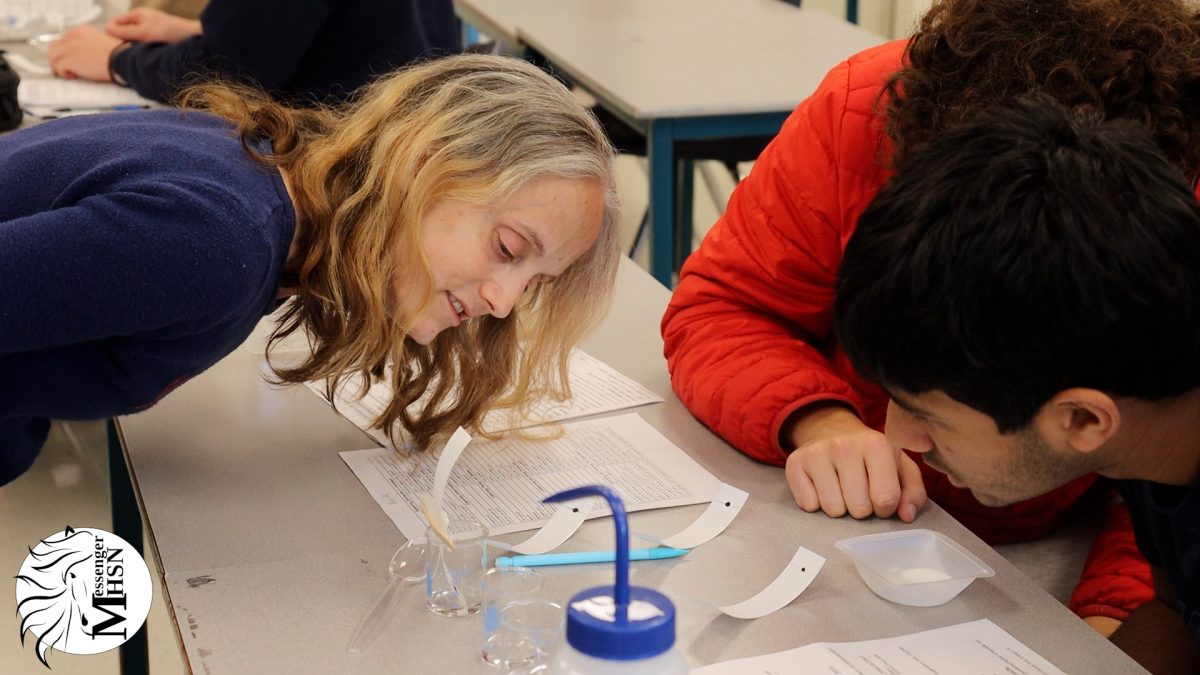

Ricardo Arjona, sophomore, attended a private school in Spain until the sixth grade before moving to the U.S. before seventh grade. His parents paid for half of his tuition, and the Spanish government covered the other half. Arjona said his schoolwork in Spain was much more difficult than here in the U.S.

“In sixth grade, I used to study for hours just to get B’s and A’s,” Arjona said. “Now, I only study for an hour and get decent grades.”

Dr. Peterson said there is not enough information to determine a concrete reason behind why many countries are outperforming the U.S. in terms of primary and secondary education.

“The economic and social benefits of a better school system don’t come over night, as students need to finish school, pursue further schooling and enter the workforce and the larger society before the positive impact of a stronger educational experience become apparent,” Dr. Peterson said. “But in the long run, the benefits of better schools are breathtakingly large—one of the most important elements for a prosperous nation in the twenty-first century.