In-Depth: Voices of Black Students Enduring Racism, Inequity

Media by Eboni Barrow

Eboni Barrow, senior, grappled with the amount of student diversity in RSD, and the district’s lack of a formal stand in solidarity with students of color following the protests against racial injustice. “Having colored people in the community, you should care about what’s happening because racism can affect a student in Rockwood,” Barrow said.

Sepo Chuunga, junior, was shattered. Footage of summer protests and uprisings made her nervous and desperate. She imagined her father and brothers embodying hashtags—victims of police brutality.

Following the killings of unarmed Black Americans such as George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, Chuunga became more aware of the treatment of Black people by police. As an African American female and Zambian immigrant, she fixated on racial injustice.

“I am a proud Black woman, but it’s concerning how many stories I’ve heard of Black people killed because of their skin color,” Chuunga said. “I’m always scared for my dad and brothers because they are my everything. I don’t want them to think they’re not enough because of their color.”

Chuunga’s experiences with racial tension in the local area has been reminiscent of her student life, where she has noticed racism, racial microaggressions and stereotypes.

She said some MHS staff view or treat her differently because of her race, and it’s difficult to avoid acknowledging it. To her, Black students deserve equality at MHS.

Chuunga is often the only Black student in her rigorous classes. She has felt unwelcomed when teachers have doubted her interest in challenging courses or when students questioned her presence in advanced classes and mocked her academic abilities.

Chuunga is not alone in her experience as many others have observed and endured racism and inequality to which the district is responding.

Racial Inequality in Education

Comparable to national statistics of educational disparities based on non-Black teacher bias of Black students, the district faces racial discrepancies regarding suspension, discipline, and academic composition figures.

In RSD, Black students are 8.7 times as likely to be suspended as white students, and generally, three academic grade levels behind white students, according to ProPublica.

Black students make up 9 percent and white students make up 78 percent of RSD. Black students account for 2 percent of the Gifted & Talented Programs and 3 percent of the AP Course Composition, while white students account for 75 percent and 82 percent respectively.

MHS has the second highest ranking of racial disparities among the RSD high schools. White students are 3.5 times more likely to be enrolled in an AP class than Black students, and Black students are 5.7 times as likely to be suspended as white students.

Chuunga said the school culture maintains the perception of a lack of performance by Black students. Inadequate coverage of Black communities in curriculum has led students to voice false stereotypes toward her, such as her family needed to immigrate from Zambia because they were impoverished.

“I’ve been going to predominantly white schools my entire life, so bullying and racism is nothing new,” Chuunga said. “It makes me angry when the administration does almost nothing to ensure racist situations and statements stop happening.”

She has seen more students contribute to racial issues and biases than those who have tried to improve them. She said MHS needs to address racial injustices and interactions with police as students of color want to trust and feel safe in school.

Concerns of Safety and Appreciation

RSD District Safety Officer Tyrone Dennis is balancing his background as a retired police officer of 16 years and his perspective as a MHS graduate, Class of 1997. The new hire said he hopes to create a sense of security by implementing programs, plans and staff trainings.

The St. Louis City native was a Voluntary Interdistrict Choice Corporation (VICC) student. He said teachers were disconnected from his city life, especially when he navigated gang-infested streets and missed sports practices to earn money for Prom.

“Those disconnects cause some VICC students to fall by the wayside,” Dennis said. “As a white teacher growing up in West County, you don’t know what a Black student needs if you’ve never been around Black people.”

Interacting with police and observing gangs in his youth allowed him to develop a lesser biased lense as a gang detective in the Atlanta Police Department. Dennis said people may avoid discussing systemic racism due to guilt or discomfort about their privilege.

Involved in community service since high school, he strives to create a sense of empathy from a racial and a law enforcement standpoint. He said it’s critical to invest in opportunities for Black students at young ages to increase inclusion.

Dennis founded Clippers & Cops, a program for police and community conversation in barbershops. This initiative aimed to enhance community relations and promote equitable racial treatment by allowing citizens to pose uncomfortable questions.

He intends to have conversations with RSD staff to strengthen their understanding of Black students and societal issues. Dennis said staff needs to begin making gradual changes so students of color can feel socialized, connected and safe.

”I like pushing the envelope as far as I can to help people understand problems,” Dennis said. “It’s all about inclusion and making people feel love across the board.”

Eboni Barrow, senior, said being president of Marquette Academic and Cultural Club (MACC) is a crucial reason she wants to go to school. She said she feels connected to other Black students experiencing racism in the community.

MACC signifies inclusion and appreciation for students of color. However, she said the club’s role must extend to everyone through self-education of cultural and racial issues.

When it can boost their image, RSD will make Black students feel respected and connected, she said. For example, the VICC Salute to Excellence in Education Awards celebrates VICC students’ achievements in July. She said this is ingenuine as it isn’t held while school, nor are the awards largely recognized.

“Black people bring a lot to Marquette, and we make the environment better,” Barrow said. “In sports and activities, different races and ethnicities allow Marquette’s name to be known. If the minorities vanished, Marquette wouldn’t be seen as it is today.”

Acknowledgement of Racism and Inequity

Sophomore Principal Carl Hudson, the only Black certified MHS staff member, said the district doesn’t normally encourage discussion of racism or racial inequity. After the death of Michael Brown in 2014, Hudson was advised by RSD not to speak of or have a comprehensive conversation about the incident.

Hudson said it’s imperative everyone contributes to discussion in classes, clubs and in the MHS community. The killing of George Floyd captured the hearts of white people, he said. The societal support for Black people could be mirrored in MHS by elevating students of color.

“One of the concerns I have is that kids will want to talk, but if staff doesn’t feel comfortable, those questions will go unanswered,” Hudson said. “To be a well-rounded educational institution, we have to be prepared to talk about what’s bearing on students’ minds.”

He aspires to serve as a source of reconciliation for students by starting school-wide, monthly discussions on social issues. He said racial injustices and biases are present in MHS because racism exists in all levels of institutions.

One of the concerns I have is that kids will want to talk, but if staff doesn’t feel comfortable, those questions will go unanswered. To be a well-rounded educational institution, we have to be prepared to talk about what’s bearing on students’ minds.

— Sophomore Principal Carl Hudson

“I’ve seen racism shown in how kids interact, making racially insensitive remarks, which happens on a bi-weekly basis when students are in session,” Hudson said.

As Black staff members and administrators retire, Hudson said RSD and MHS must be ready to assume the responsibility of supporting students of color.

Sarah Abbas, senior, said MHS lacks in celebrating and connecting to students of color, especially by not hosting a Black History Month event last year.

For more than five years, MHS has had 99 percent white teachers and 1 percent hispanic teachers, according to the RSD Human Resources Department.

Abbas said that as a Pakistani Muslim American, the lack of racial diversity in staff and curriculum adds to representation failures.

“The lack of diversity takes a toll on you,” Abbas said. “It’s ingrained in your mind you aren’t capable of doing what everyone else can. People of color are seen as the troubled kids because they’re the majority being disciplined. It puts you at a disadvantage and allows you to think you’re inferior.”

She has experienced interpersonal racism, harassment and bullying at MHS along with others. She said she knows Muslim, Hijabi and Black students who have sought out staff assistance and received little to no accountability.

Overcoming Shortfalls in Staff Support

Without a formal statement from RSD in solidarity with Black students following the summer protests, Abbas said RSD falls short in openly discussing and addressing racial issues.

“When you’re in a class with someone who is racist, you’ll be so uncomfortable, especially when you’re stared at and talked about,” Abbas said. “It makes you scared your school can’t stand up for or protect you in the place you spend eight hours a day.”

One of the biggest concerns for Jennifer Curtis, Special School District teacher (SSD), is students of color not feeling accepted. Her main goal is to aid minority students in the pursuit of justice and support this year by having uncomfortable conversations.

We have the power to expose all of our students to opportunities, and I would be heartbroken if we lost this momentum. We need diversity because you shouldn’t be able to not have had Black teachers or seen who you can become.

— Jennifer Curtis, Special School District teacher

As a white teacher, she said there is a racial bias from educators onto Black students.

“It’s hard to see racism and bullying in public and the consequences, if any, are private,” Curtis said. “In my class, when a kid said something racist, I called them out and asked what they meant to ensure everyone knew that it was not okay.”

Curtis incorporates racially diverse research, novels and student perspectives in class to spread awareness of racial and cultural differences.

In a parent-teacher conference, a white parent told Curtis to avoid the idea Black and white people are socially equal as it made her son uneasy. She said teachers cannot decide when to address racism, and RSD must stand by anti-racism amid community pressure.

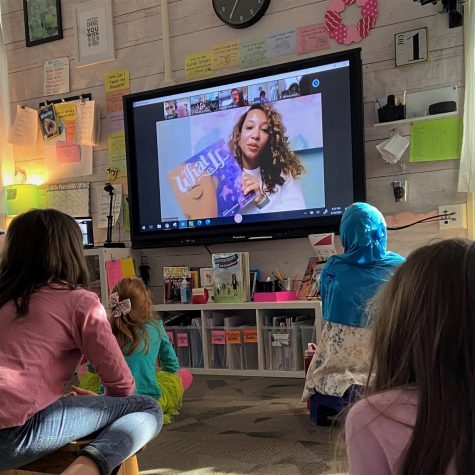

For instance, a parent of Pond Elementary School complained about the book Ron’s Big Mission, featuring the only Black member of the 1986 NASA Challenger crew, read in a second grade class. Principal Carlos Diaz-Granados responded by reading the book to the school.

“We have the power to expose all of our students to opportunities, and I would be heartbroken if we lost this momentum,” Curtis said. “We need diversity because you shouldn’t be able to not have had Black teachers or seen who you can become.”

Having served on interview committees for new staff in the past few years, Curtis said candidates from RSD are mostly white, even for last year’s Assistant Principal position.

The district is holding its fourth annual Diversity Job Fair this February as well as implementing their “Welcome Home” program to encourage recruitment of educators of color.

The RSD teacher of color gap is 21.5 percent as students of color account for 23.5 percent and teachers 2 percent of the RSD composition, according to data from the Missouri Department of Elementary & Secondary Education and the National Center for Education Statistics. Similarly, the vast majority of Black students face a teacher gap in the U.S.

Strategies to Address Racial Issues

Dr. Paul Gorski, associate professor of Integrative Studies at George Mason University, said the first step for accountability is hiring teachers committed to equity.

“The problem for schools is they’re rewarded for the optics of racial equity, not for their actual commitment,” Dr. Gorski said. “Oftentimes, the people hiring don’t have the expertise to recognize when someone is demonstrating they’re going to be a problem.”

Dr. Gorski’s research found most teachers aren’t trained to effectively respond to racism, racial bias and inequity. He said the comfort of white educators is prioritized over that of students experiencing racism. Teachers avoid addressing racism in fear of repercussions.

Due to increased societal awareness of racism, Dr. Gorski said many schools are performatively investing in change. He hasn’t seen enough progress for anti-racism, which he connects to schools only celebrating cultural diversity and competency. Without assessing a school’s procedures, policies and culture for racial bias or inequity, systemic racism will fester.

Teachers tend to have significant racial bias, he said. When combined with subjective decisions, such as recommending Black students for classes or interpreting their behavior, disparities deepen in achievement and discipline rates.

Educator’s racially biased choices accumulate to manifest institutional racism. He said deficit ideology, where teachers attribute educational disparities by identifying deficiencies in students, is common.

“This looks like saying ‘white students are doing better on standardized tests than African American students’, and racially biased white teachers think ‘we have to fix African American students and their families’.” Dr. Gorski said.

Schools districts who are models for equity conduct anti-racism professional and leadership development, write and apply equitable discipline policies, and hold racially biased teachers accountable, Dr. Gorski said.

RSD Director of Educational Equity and Diversity Brittany Hogan said she saw many of Dr. Gorski’s identified detours to improving racial equity in RSD such as fixating on cultural diversity, prioritizing educators’ comfort and claiming the ‘color-blindness’ ideology.

Black students are judged as a collective, she said. Her awareness of Black students’ life experiences allows her to disrupt stereotypes and promote equality. Hogan said the districts’ racial disparities in discipline and inclusion of students of color in class needs improvement.

She said institutional racism in education prevents teachers from believing Black students can manage advanced work and dismantling misconceptions.

“We have the responsibility to allow children to see reflections of themselves in all aspects of their educational community,” Hogan said. “We have the responsibility to show kids the windows of the world. Diversity is good for every student because everyone won’t look like you in the real world.”

Under RSD superintendents Dr. Eric Knost and Dr. Mark Miles, she said conversations about social-emotional learning as well as honoring, protecting and caring for students have progressed significantly.

All guidance counselors, social workers and administrators participated in Anti-Bias, Anti-Racism training (ABAR) this spring, and will attend their second set of sessions this fall.

Hogan said RSD and MHS educators will be ready to have quality conversations. Educators are working toward being trauma informed, breaking their own barriers and finding their truth or reconciliation about their beliefs.

“If you say you love Black kids, then you can’t act like you don’t see the injustices happening against them,” Hogan said. “We don’t have time to wait to be comfortable to make things better for the children because I don’t know how long that will take.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Marquette High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs. You may become a PATRON by making a donation at one of these levels: White/$30, Green/$50, Blue/$100. Patron names will be published in the print newsmagazine, on the website and once per quarter on our social media accounts.

Lauren Pickett, senior, is the In-Depth Editor for the MHS Messenger. This is her second full year on staff. Also, Lauren participates in two other activities:...

Emily Chien • Mar 18, 2021 at 1:26 PM

This is outrageous, it’s time a change needs to be made. Not only had MHS faced racially insensitive incidents but many other Rockwood schools have as well. It’s almost as if racism runs in the culture in this district. ABAR is a great new change and a step forward for our community, I also suggest two meaningful changes as well. One, Rockwood students begin to take liability and responsibility for their racist actions. Two, teachers begin to educate students about racism. (Not just racism in history but modern racism.) I created a petition for these specific reasons, I would love it if you could support and bring the attention it deserves.