Black History Month: How Silence Spoke Louder Than Words

Media by Lauren Pickett

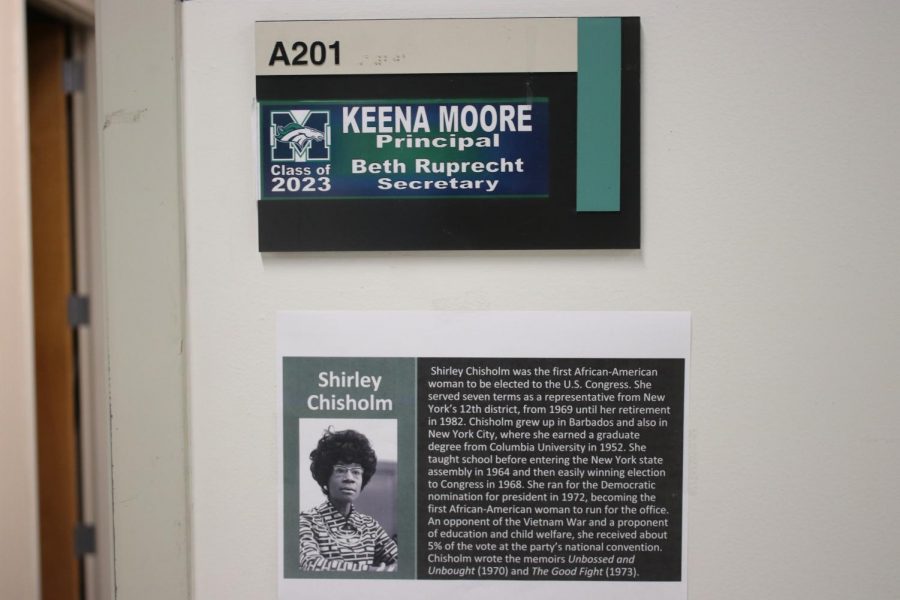

The name plate of Freshman Principal Keena Moore is atop a paper presenting Shirley Chisholm, the first African American U.S. Congresswoman. Both Moore and the paper demonstrate a lack of full representation in MHS as Moore is one of two African American faculty members in a high school of 2,250 students, and Chisholm’s paper is one of a couple scarce posters scattered around a three-story building. This is how MHS carried out black history month.

As February, the month reserved for acknowledging black history, fades into March, I found these last 29 days only provided me with feelings of shame and resentment.

These emotions stem from the mistreatment of Black History Month at MHS, which held no events, spurred no conversation, created no coverage and made no announcements or attempt to go beyond what the curriculum and policy required.

This inaction reflects not only the lack of value in black students’ educational and historical representation, but also it exposes the degradation of the standard of diversity regarding administration and faculty necessary to maintain an inclusive, supportive atmosphere within these school’s walls.

High schools, like MHS, should be informed they are failing their black students and the legacy of Black History Month by allowing racial and diversity issues in education and employment to sink to the bottom of their to-do lists.

Until they formally address their lack of teacher and staff diversity, black students’ potential will continue to be stifled, schools will be deprived of vital perspectives and aspiring minority educators will remain discouraged from applying to schools who don’t commit to inclusion practices.

A 2018 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research concluded having one black teacher lowered black students’ high school dropout rates and increased their desire to go to college and likelihood to enroll in college. The study also found black teachers are more likely than white teachers to have higher expectations for black students.

Without black teachers, who is there to help close the achievement gap by supporting and understanding black students? Who is left to find meaning in black history and make a commitment to incorporate it in students’ education? Who is available to introduce and answer those uncomfortable racial and cultural questions?

High schools, like MHS, should be informed they are failing their black students and the legacy of Black History Month by allowing racial and diversity issues in education and employment to sink to the bottom of their to-do lists.

Moreover, this problem has extended across the entire country, according to the Southern Poverty’s Law Center’s (SPLC) Teaching Tolerance 2014 project, “Teaching the Movement”, which evaluated and compared every state’s standards and curriculum resources regarding the civil rights movement.

The study found 20 states received a grade of an “F” for earning a 20 percent or below on their standard of civil rights coverage, including Missouri, with a score of 14 percent. This grade could mean states didn’t reference the movement or missed essential information in their instruction.

Although this may not be reflective of the district, it demonstrates the magnitude of this injustice as local schools also contribute to our disappearance from history.

No longer should MHS be able to front their top tier rankings such as a overall rank of “Top 5 percent” out of all Missouri public schools because their 27 percent minority enrollment, slightly under the state average, according to a Public School Review 2020 report, represents more than numbers can tell to those who haven’t set foot within the school.

These numbers cannot paint my experience as a black student, who has never witnessed a black teacher set foot in the classroom, nor saw themselves deeply expressed in the curriculum, or felt academically adequate, encouraged or valued to the level of my racial counterparts.

In my years of schooling, my courses failed to integrate black and white history in the same time periods. Often excluding important black figures who made crucial advancements from art to mathematics and skipping through 400 years of enslavement, these curriculums paint black history as minor and its culture as one dimensional.

Some argue Black History Month is unnecessary due to modern advancements within the black race. However, an embarrasing statistic articulates why we cannot afford to relinquish Black History Month, or diminsh the fight for staff diversity and improved requirements: Only 8 percent of high school seniors could identify slavery as a main cause of the Civil War in 2017, according to Teaching Tolerance.

The overemphasis on white history shapes students who grow up believing black history isn’t important information as it rarely makes it into the quick, often times challenging curriculum—especially for it to be only sufficient to talk about black people and their issues during the one (shortest) month of the year.

As a result, even black students are blinded from the importance of their ancestors unless they decide to study their history outside of school. We already look forward to February, a time to gather the scraps of attention toward black issues left on the table of a whitewashed curriculum. This year, we were starved.

If we dedicate time in standard classes to learn black history and culture, not segregating it into an elective to be further disregarded, we could produce well-informed leaders who better understand racial issues and how society has preserved structural racism and oppression, contrary to what the textbooks tell them.

This could alter the negative societal views of black people, create more connections among races and heighten movements for change in support of them.

In order to regroup and prepare for next year, educational systems must take action and commit to diversity and inclusion for district personnel and policy and educate on black history without expecting their minority groups and student organizations to make the first step.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Marquette High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs. You may become a PATRON by making a donation at one of these levels: White/$30, Green/$50, Blue/$100. Patron names will be published in the print newsmagazine, on the website and once per quarter on our social media accounts.

Lauren Pickett, senior, is the In-Depth Editor for the MHS Messenger. This is her second full year on staff. Also, Lauren participates in two other activities:...