A Journey From Another Hemisphere: EL Students Share Their Stories

Media by Victoire Lehee

Living an active life outside of school, Victoire Lehee said some of her favorite pastimes are hiking, running, and horse riding. She has ridden horses for about seven years and finds time to practice primarily on the weekends. In Switzerland, Lehee said she focused on her horse jumping skills. Now living in the U.S., she was able to find a new barn where she mostly works on dressage. She sits atop her horse, Lingotton, pictured above. “Horse riding teaches me perseverance because sometimes the horse doesn’t want to do things, and you can’t be angry, so I think I learned patience too,” Lehee said. “When we’re together, I feel like the horse understands me, and you don’t even have to talk.”

Victoire Lehee, sophomore, connects with her French roots by speaking her mother tongue at home and speaking either English, German or Russian outside depending on her global location.

Lehee represents the almost one out of every four children in the U.S. who speaks a language other than English at home, according to an analysis of national data compiled by the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Kids Count Data Center in 2018.

She was born in France and lived in Moscow, Russia, for eight years; Zagreb, Croatia, for four years; and Lausanne, Switzerland, for another four years. She, her parents and her younger brother moved to the U.S. last fall for her father’s job opportunity with Nestlé Purina Petcare, leaving her older brother behind in Switzerland.

“I really enjoyed living in Switzerland because of the peace, and I loved the view because we saw lakes and mountains every day, everywhere,” Lehee said.

Now, she can reminisce on her various experiences across the Atlantic Ocean as an English Learner (EL) in the RSD English Language Development program (ELD), where students, often migrants and immigrants, are supported for English development.

Multiple government databases report an increase in enrolled EL students in schools in recent years. These learners may supplement classrooms with cultural and ethnic diversity from their experiences.

For instance, the National Center of Education Statistics found the percentage of public school students who were ELs was higher in fall 2016 than in fall 2010 in 35 states and the District of Columbia.

Concerning her past in the European regions, Lehee said she has vague, yet good memories of living in Zagreb and attending a British elementary school while in Moscow, but she can more vividly recall her time in a private Swiss high school, which aided her English fluidity.

“Switzerland was really small and calm,” Lehee said. “My school had about a hundred people. My classes were also quite small, and we had the same people in each class.”

She acknowledged challenges in coming to MHS. She was foreign to the variety of courses, the complexities of student schedules, the large classrooms with unfamiliar faces and the new technology, like Chromebooks, which contrasted with her previous handwritten assignments.

Lehee said she misses aspects of French culture in Croatia and Switzerland, such as the hospitality and the friendly relationships cultivated by the preference to walk to destinations with others rather than using a vehicle.

Concerning Zagreb and Lausanne, she also misses going to the beaches and French bakeries and celebrating French holidays with her community. Also, bi-monthly, students would have two weeks of holiday breaks outside of school and weren’t assigned much homework.

Lehee said it was difficult to have frequent learning interruptions, and she likes having fewer breaks, receiving homework assignments and taking quizzes often unlike the structure of curriculums in the other schools.

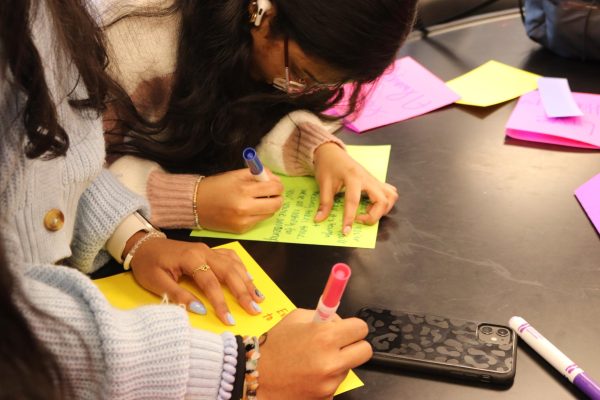

Working with English Learners of Other Languages (ESOL) helps improve her oral and written skills through vocabulary lessons and speaking presentations, Lehee said, as well as provide her with a group of friends and a helpful teacher.

“ESOL is a separate class, and not a lot of people are aware of it,” Lehee said. “But it is a class of many cultures and with people from many countries.”

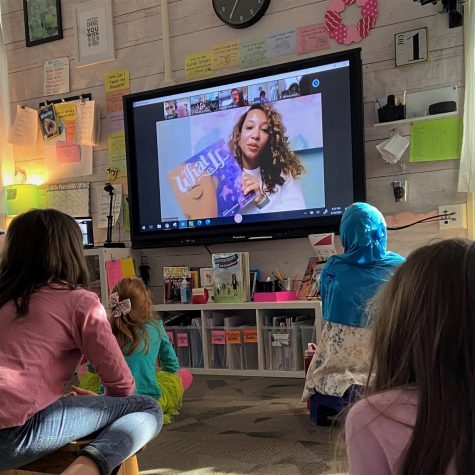

Carol Logue, ESOL teacher, tends to the social, personal and academic needs of EL students by teaching them about various aspects of the culture and being available however they need assistance.

Teaching for 28 years since 1992, Logue was inspired to teach after hearing immigration stories of her father’s great-grandparents from Italy, and she desires to help students similar to how her relatives were helped coming to the United States.

“It’s my life’s blood, it’s the best,” Logue said. “I’m so happy to hear what they have to say. It’s a great pleasure beyond belief when a student will raise their hand and ask a question. That’s always quite a milestone for me, and it touches my heart.”

Logue sees the ESOL program growing often, especially concerning foreign affairs.

“It depends on what’s going on in the world each year and why families decide to leave their home countries and come to the U.S.,” Logue said. “Sometimes we have a lot of Spanish speaking kids, some years we have Russian speaking kids, and we’ve had Arabic speaking kids.”

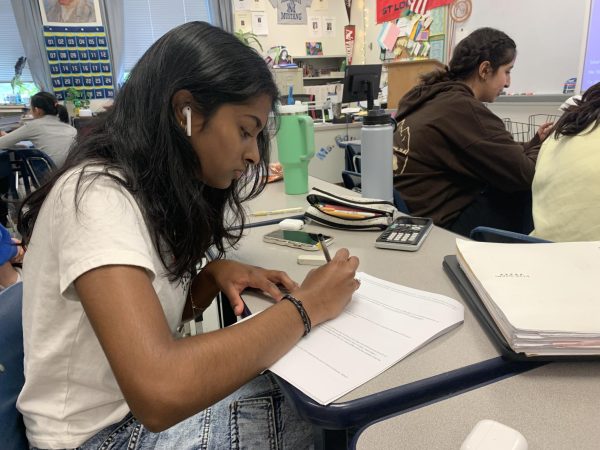

Former EL student Mahdiyeh “Bahar” Safarzadeh, junior, speaks Persian and said she represents her culture even in her names: “Mahdiyeh” is of Arabic origin meaning “who is guided,” and she goes by her nickname, Bahar, which means spring in Persian, the season she was born.

Safarzadeh, her parents and her older brother lived in Iran until she was a preteen, and she was born a Muslim although the family secretly practiced Christianity amid the majority Shi’i Islam practicers in the Islamic Republic.

Having secret access to prohibited television channels undermining Iran’s systematic Islamic censorship of the media and her family who remembers the past with limited oppression, Safarzadeh said Iranians previously experienced a degree of Western-like culture concerning movies, music and freedom with clothing, such as not wearing a hijab.

She said she felt disconnected from the current culture and government corruption as she became informed of cultural freedoms prior to the Islamic Revolution of 1979 in Iran, which she references as a turning point.

“Iran has a really nice and really rich and beautiful culture,” Safarzadeh said. “Right before the Revolution, we were the most flourishing and developing, and we almost had everything we could.”

Her feelings of separation continued as Safarzadeh said she experienced the stigma and stereotypes associated with being a “devote Muslim” in school, such as attending classes teaching the Quran and praying multiple times a day.

She was bullied for being Christain, and although she said she didn’t want to pretend to be Muslim, she gave into the social pressures and religious expectations.

“I used to wear this headband that had a flower on it, and a school dean came up to me, took the headband and sent me home just because it had a flower,” Safarzadeh said. “I was so hurt. I used to start wearing things that completely hid my hair, and I used to go to the mosque often to show I was fitting in with the normal people.”

Around 2013, the plight of being a religious minority in Iran’s Islamic theocracy caused Safarzadeh and her family to flee to Turkey as refugees under the United Nations Refugee Agency’s protection for a year and a half. However, she couldn’t escape bullying in school due to her religious beliefs.

“My social life was affected most by my travels and going through this process,” Safarzadeh said. “It definitely hurt my self-esteem because I feel like I’m being judged all the time because of who I am, I’m still trying to fix that. I tell myself I should be who I am, and I’m not ashamed of it.”

Once Safarzadeh and her family migrated to the United States in 2015, she began struggling with taking care of her parents due to their language barrier.

“Here I am living as an American, and at home, I’m living as an Iranian person, and it’s two different lives you have to balance,” Safarzadeh said. “I kind of have to run things in my house for things like banking problems, loans and insurances.”

She said it’s frustrating being designated “the family translator” and not being to live like an average teenager, but it may be beneficial in the future to have these experiences.

Safarzadeh also said the American style of education is unknown to her parents, and now alone, faces the dilemma of choosing a career of her passion or a career with stable income.

“I want to support my family, and it’s going to be hard,” Safarzadeh said. “My dad and mom have been through so much, and I want to get to that point [of success], so they don’t have to work as hard as they do right now, and that’s always on my mind.”

Although she said her parents want her to have a job where she’s happy, being a first generation immigrant makes her feel as though she may disappoint them if she’s not highly successful and educated now going to school in the United States.

Her education in Missouri began in Wydown Middle School and then into Parkway Central High School, where she worked with their ESOL programs until she transferred to MHS during her sophomore year and no longer needed assistance.

She said she came to the MHS ESOL room because a student guide Hashim Rozi, Class of 2018, said she may meet people with similar situations, and now she’s a regular visitor. She said at MHS, students were not as empathetic toward her situation and didn’t allow her to feel as accepted as in previous schools.

“People won’t really care about [ESOL] if they’re not interested in it,” Safarzadeh said. “I wish there was a way to get people to become more interested in other cultures because they tend to just walk by us without taking their time to understand. I just wish there was more awareness.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Marquette High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs. You may become a PATRON by making a donation at one of these levels: White/$30, Green/$50, Blue/$100. Patron names will be published in the print newsmagazine, on the website and once per quarter on our social media accounts.

Lauren Pickett, senior, is the In-Depth Editor for the MHS Messenger. This is her second full year on staff. Also, Lauren participates in two other activities:...