When Marina French, sophomore, went to the SLCL Teen Book Festival on Saturday, Dec. 7, she was upset to hear authors talking about how their work was getting banned for unfair purposes.

“One author talked about how schools were banning her book for sex when none existed in her novel, how authors are getting refused from school meetings just because schools released the book was queer, and so many other injustices,” French said.

10,046 books were banned in the 2023-2024 school year, a 6,684 book or 66.5% increase from the 2022-2023 school year, according to Pen America. Bans most commonly cite LGBTQIA+ characters, mental health, substance abuse, suicide, sexually explicit content and more as the reason.

According to the American Library Association, between January 1 and August 31, 2024, there were 414 attempts to censor library materials, with challenges against 1,128 different titles. In 2023, during the same time period, there had been 695 attempts to censor material and 1,915 different titles challenged. While there were less in 2024, these numbers are still higher than they were pre-2020.

Most recently, ABC News said the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights will no longer be offering guidance through book bans and coordinators will not be employed to investigate illegal book bans.

Brittany Sharitz, librarian, described a book ban as when a book is removed from an institution, typically a library.

“Usually a ban is supposed to go through a process before it’s just removed for it to be an official ban, but some organizations may not always follow the right steps every time,” Sharitz said.

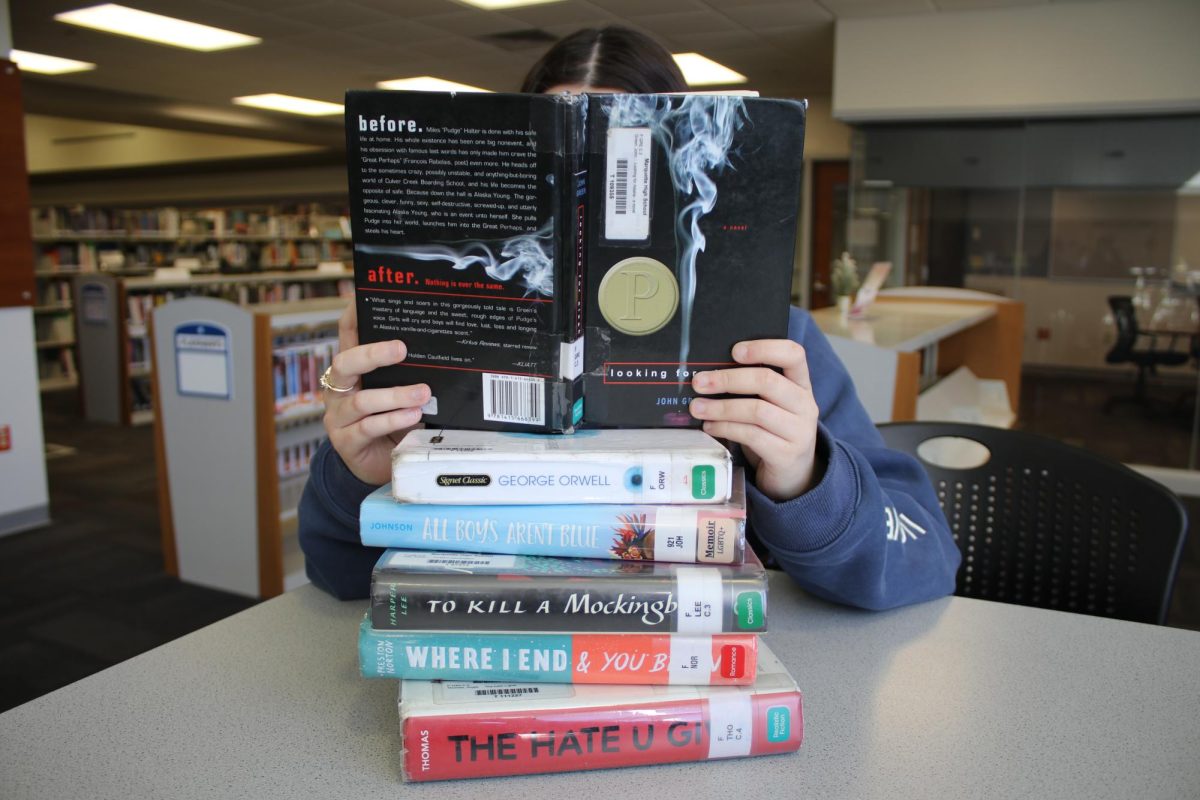

Although there haven’t been any books banned at MHS as of now, there have been multiple books that have been challenged, especially in the 2021-2022 school year. According to Rockwood’s material challenges list, some of the challenged titles have included “Crank” by Ellen Hopkins, “Gender Queer” by Maia Kobabe, and “All Boys Aren’t Blue” by George M. Johnson. All of these challenges have been resolved.

There are some titles that school libraries are not allowed to own due to the Missouri State Legislature. According to St. Charles Community College, this legislature bans any type of sexually explicit material. This law also declares that it’s wrong for school officials or any school visitors to distribute any material that is deemed harmful to children.

According to an article posted by the Daniel Boone Regional Library, these titles include “Flamer” by Mike Curato, “Watchmen” by Alan Moore, and “The Sacrifice of Darkness” by Roxanne Gay.

Sharitz said the pandemic had a lot to do with the increase in book bans.

“We didn’t have a good control of how we wanted to live,” Sharitz said. “I think that combined with the fact that students were at home and parents were hearing more of the lessons being taught, I think parents decided that they wanted more control over something in their lives and the education of their students was an easy thing for them to say, ‘I’m going to control this’.”

Lillian Sobery, sophomore, considers a book ban as when a book isn’t available for people to read.

“I feel like the reason people ban books is because they don’t agree with what’s in the book or they don’t think that a certain age level should be reading it,” Sobery said. “While all that might be true, you don’t need to outright get rid of it.”

Sobery also said she doesn’t feel that there’s a valid reason for banning books.

“I feel like without [books], it takes away from the knowledge that people could gain from reading them,” Sobery said.