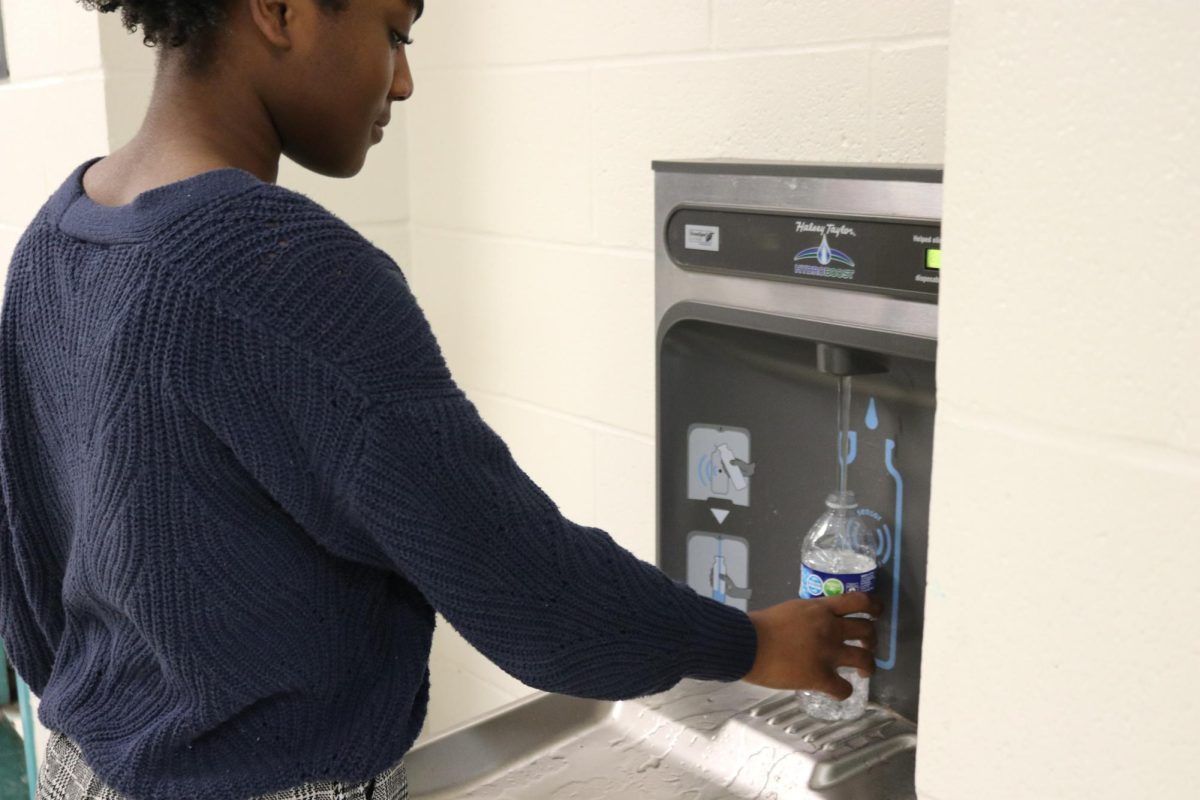

In response to the “Get the Lead out of School Drinking Water Act,” district maintenance crews tested and repaired water outlets last year that were above the new standard.

At MHS, 88 water outlets where people are expected to drink from were tested. Samples from the left sink, big steam kettle faucet and jug filler in the kitchen tested above the standard of 5 parts per billion (ppb), according to the Rockwood School District Department of Health and Wellness.

After flushing, two of the lines had acceptable ppb, but one still tested above 5 ppb. Junior Principal Kyle Devine said this line has been shut off until repairs can be made when the building is shut off.

Lack of use is part of the reason why some lines had a higher ppb than others.

“[Ppb] is going to go up on things that are not used often,” Devine said.

Coy King, Environmental Program Specialist at the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, is a program coordinator for the Get the Lead Out of School Drinking Water Act.

“Children are susceptible to neurological and health effects of lead contamination,” King said.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Missouri Department of Natural Resources monitor lead in drinking water in public water systems. The Act now requires all public schools to complete inventory, sampling and remediation of all drinking water outlets for lead contamination.

The Act was passed with a goal of preventing the negative consequences of ingesting lead.

The standard of 5 ppb was proposed to be lower, but there were some technological issues in meeting that decreased level, King said. King said that all public schools are required to report how many samples they took, how many of those samples were above 5 ppb and how the school remediated the issue.

“I’d like to see us fine tune that legislation to make it more understandable to the public school system,” King said.

Rockwood has a contract with the Missouri Department of Health and Human Services to receive funds to help with the process of testing and remediating water outlets, King said. Other districts have also received funds.

“We are here to assist those school districts,” King said.

Jack Neier, sophomore, said lead is less of a concern of him than other issues at MHS, such as the locker rooms.

“Not the worst thing that’s been in my body,” Neier said.

Lead is a heavy metal and is toxic to the body, Jessica Hutchings, chemistry teacher, said. Its positive charge determines what it will react with.

While the symptoms and toxicity levels of lead are known, other elements are not.

“Some of the actual chemical mechanisms of what specifically is going on with the body are not as well known or studied,” Hutchings said.

Lead is most commonly found in pipes or older paints, specifically white or yellow.

“If the paint chips off, and a little toddler ingests it, that’s a problem,” Hutchings said.

To remove lead from water, filtration or reverse osmosis, a specific filtration method, can be used. People can also use a water filter to remove lead from water in their homes.

“It’s not quite as efficient and cheap as reverse osmosis, but those filters will specifically say ‘for lead’,” Hutchings said.

Unless a person gets treatment, lead will stay in their body and the levels will build up. Treatment for lead involves taking a pill that will bond to lead in a certain way so the body can eliminate it.

This month, signage that says “non-potable water, do not drink,” will be placed on bathroom sinks and hand washing stations that have not been tested because they are not drinking and food preparation sites.

Hutchings advises that students pay attention to the new signage.

“If something says non potable water, don’t drink it,” Hutchings said.