Your donation will support the student journalists of Marquette High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs. You may become a PATRON by making a donation at one of these levels: White/$30, Green/$50, Blue/$100. Patron names will be published in the print newsmagazine, on the website and once per quarter on our social media accounts.

Mask Usage Leads to Difficulty Understanding Emotion

February 28, 2021

Hailey Benting, senior, does not smile in the hall.

Instead, she waves and excitedly flashes her eyes at peers.

Prior to COVID-19, a smirk or saying “hi” would suffice as a proper greeting; however, these once recognized facial expressions are now lost behind a mask.

Facial expressions, Benting said, are essential to the tone or feeling of the conversation.

“A lot of the time when people say something, you can read their facial expression and know that they’re lying or they feel differently,” Benting said.

Masks can make it harder to work with other students and socialize, she said, and social distancing only adds to this communication barrier in the classroom.

Benting actively participates in classes by asking questions and for clarifications. She said masks haven’t discouraged her from continuing to talk to teachers. However, it has created a barrier between her and classmates.

“Conversation can get lost and end sooner than it should because you can’t understand what the other person is saying or you misinterpret what they say,” Benting said.

She said students tend to simply give up on confusing conversation rather than seeking clarification. Hiding behind a mask makes it easier to ignore awkward misunderstandings.

Benting said students shouldn’t shy away from these issues but instead exaggerate their behaviors more in order to be more clear.

Remaining hopeful for the future of communication, Benting said masked conversation will encourage further emphasis on tone. Masks force people to be more direct with their speech because they can’t rely on facial expressions for how they feel.

“With masks, it’s important to acknowledge misinterpretations with what you’re saying or how you’re feeling,” Benting said. “People need to emphasize clarity and emotion with their words because it’s one of the few things we have left to rely on.”

As a result of COVID-19, masks have become necessary to wear in public spaces, other students and staff notice challenges with understanding emotion and nonverbal conversation cues.

Emily Stockwell, language arts teacher, stretches her smile muscles, attempting to show a grin through her mask in class.

Normally, she greets students in the hall with a subtle smile; however, masks have made it increasingly harder for her to connect with others.

“It’s frustrating to me that people can’t truly see when I’m smiling, so I can’t wait to smile at everyone I encounter when masks are a thing of the past,”Stockwell said.

Stockwell said she encourages students to speak up if they have a hard time hearing someone because there shouldn’t be anything awkward about asking someone to repeat themself.

Sophomore Principal Rick Regina has spent many years establishing relationships with the student body and he motivates student morale by continuing “Trivia Thursday” during lunch shifts.

Regina said it is unclear if school will return to a state of normalcy by the end of this year; however, efforts can still be made to maintain safety while encouraging interaction among staff and students.

“We’ve been able to do something for 100 years in high schools in America, but now we’ve realized that some of those things we’ve done, we’ll have to do differently,” Regina said.

He said the key to restoring last year’s buzzing atmosphere is to simply talk to students everyday; Regina makes use of his classroom visits by starting the conversation and learning new names.

CHALLENGES

Stockwell’s son, Oliver, was diagnosed with moderate bilateral sensorineural hearing loss when he was 3.5 years old.

Talking in the car to Oliver, with road and radio noise interference, has been and continues to be a recurring issue. When facing a different direction in the car, sound travels away from Oliver’s seat adding to the miscommunication.

Now 8 years old, Oliver overcomes new challenges with his heavy reliance on lip reading when communicating.

Oliver has a DM system at school allowing him to hear his teacher in a hearing aid that is connected to a microphone on the teacher. Even though this sound remains muffled from the mask, Oliver’s hearing aid amplifies the volume enough so he can comprehend it.

“With Oliver, I encourage friends, family and teachers to check for understanding if it seems he may not be hearing them clearly,” Stockwell said. “As with any disability, I always think it’s best to ask the person what works for them or what you could do differently.”

She predicts this challenge will make hearing people aware of all aspects concerning communication and have a positive impact on communication in the future.

Stockwell hopes teachers and students realize the impact of visual cues on communication that we often take for granted. By overcoming challenges with masks, she redefines conversation as more than just speaking and listening.

“As far as lessons go, I think it’s so important to remember that everyone is different, and that’s a good thing,” Stockwell said. “But what we all have in common is that we’re people first.”

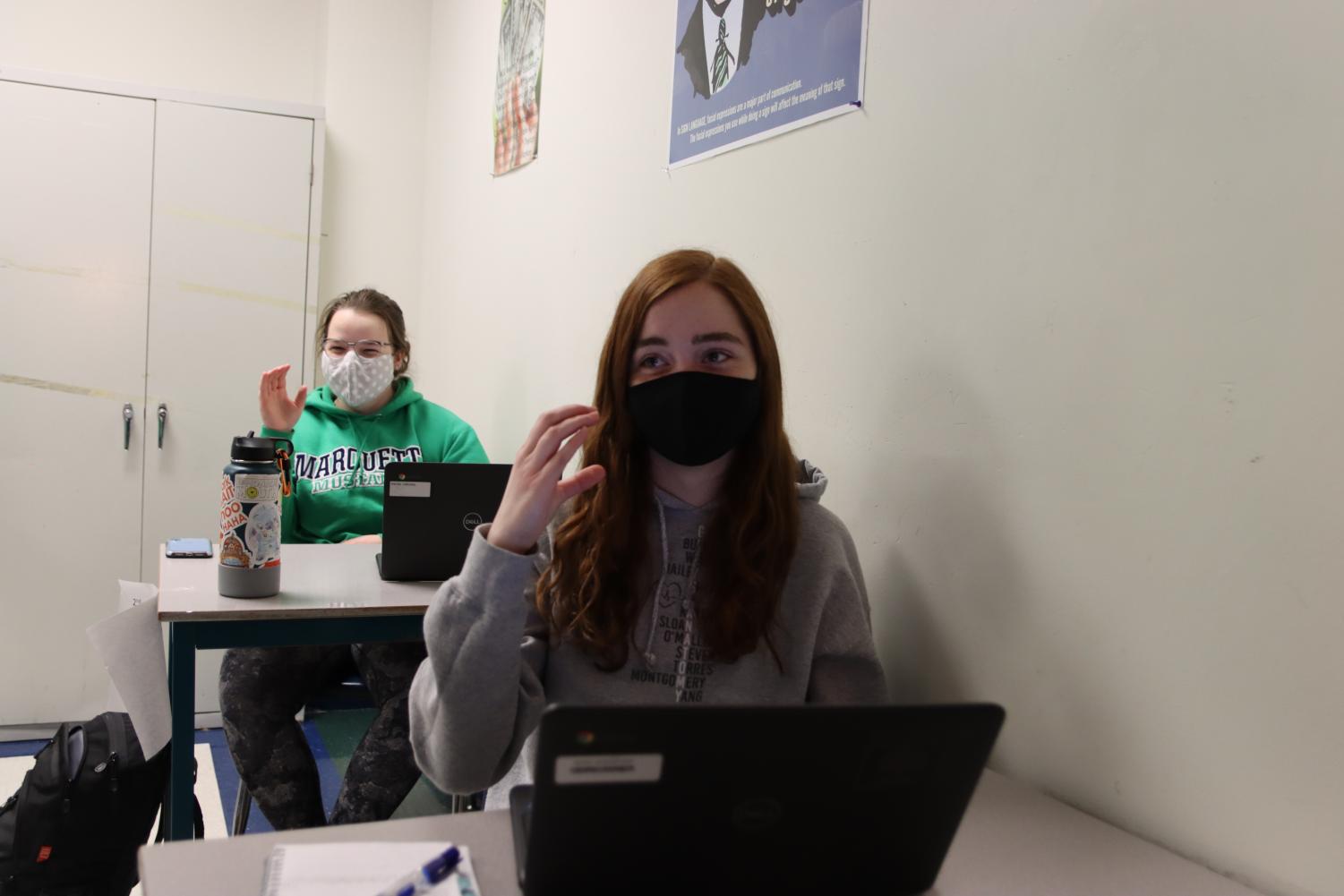

Maddie Reed, junior, Reed takes on the role of a “friend” in the Acting 1 class with students who receive SSD services, an introduction to the theatre department through acting games, with assistance from theatre involved students.

With communication through masks, Reed emphasizes how important it is to be patient and seek understanding.

“I have never really taken a class like this or really worked with SSD students at all, but one thing I learned very quickly is you can’t ask a lot of questions at once,” Reed said. “It can overwhelm the students and cause frustration.”

She finds herself asking for clarification constantly because she can no longer lip-read mumbling or quiet students. Reed said she has to work extra hard to be clear and loud as it’s the best she can do to communicate.

“I have to be more attentive and really listen rather than just focusing on subtle visual cues,” Reed said. “I have to rely more on voice to convey emotion which is not as clear.”

Similarly, Reed said she recognizes communication is a struggle for both sides of the conversation.

For students who receive SSD services, hidden facial expressions make it difficult to understand the tone of the message; for Reed, she said it can be hard to listen to mumbling.

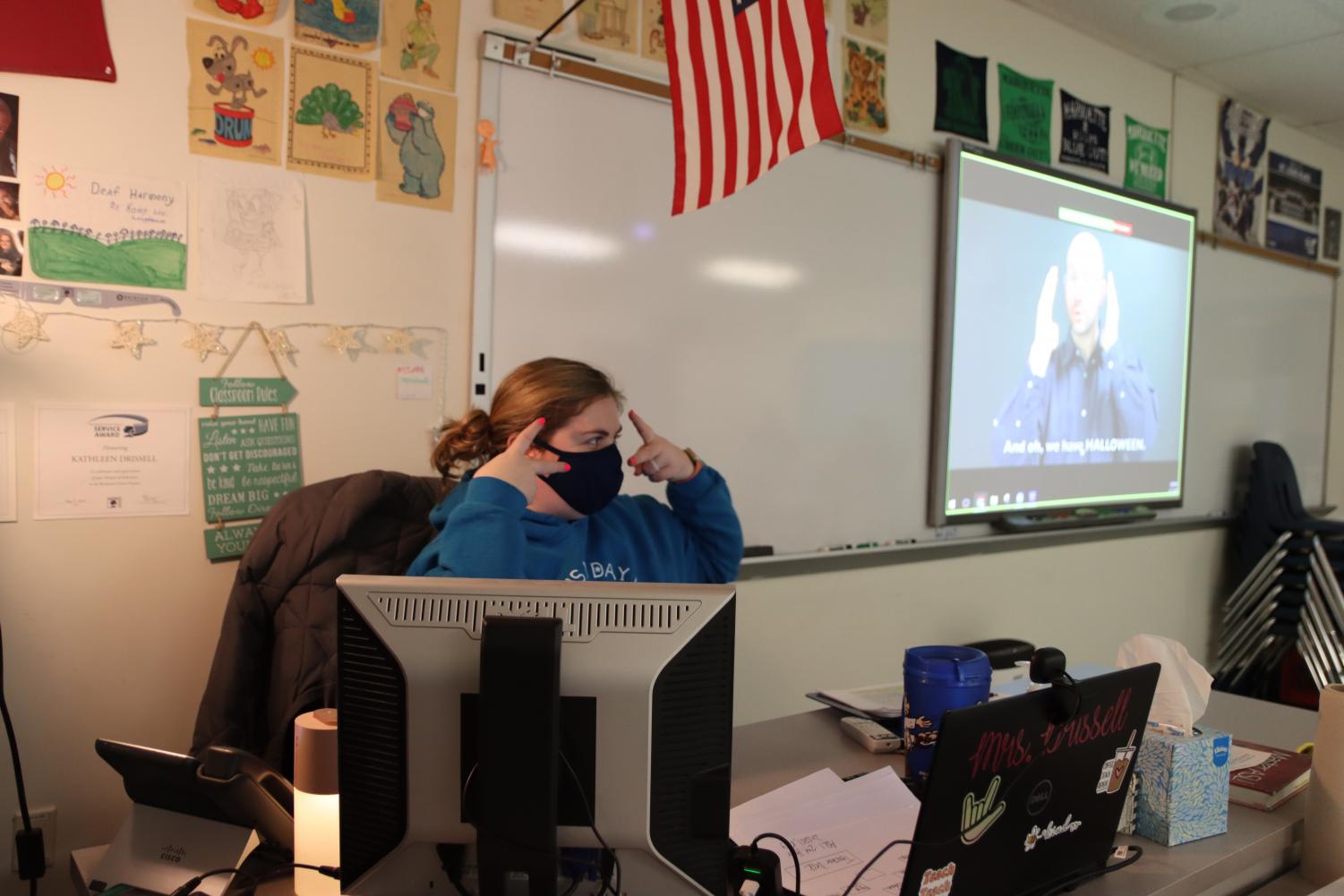

FACIAL EXPRESSIONS

As an American Sign Language (ASL) student, Carson Hanis, junior, said facial expressions are essential to practicing ASL. He said students can’t sign emotions and that feelings like disgust must be shown in the face, not with the hands.

Besides emotion, Hanis said lip reading is almost equally necessary for learning the language.

“Lip reading with ASL is very important because a lot of people in society don’t know ASL, and it can be almost impossible to communicate with someone who is deaf,” Hanis said.

He said for certain deaf people who can lip read, being able to see their mouth is much needed to communicate with members outside of the deaf community.

Hanis said wearing masks is a barrier to learning a language, even one with clear gestures like ASL because it heavily relies on facial expressions hidden behind a mask.

“Facial expressions mean everything,” Hanis said. “Many times the words that people choose do not fully represent what they are actually feeling.”

TONE

Ashley Hobbs, social studies teacher, said tone of voice remains one of the few cues not lost behind a mask.

Although this can be misinterpreted over text or email, she said, Zoom calls allow tone to be properly understood.

“Sometimes when you’re sarcastic, part of your sarcasm is that you’re not showing it on your face, so then it doesn’t read as well,” Hobbs said.

She experiences uncertainty in the halls when looking to greet a student because she is unable to recognize faces. Building relationships with students compared to years past has become more difficult for Hobbs.

Oftentimes, quick facial expressions are the hardest to read, but people have already learned the emotions conveyed with eyes. The sole reliance on eyes, Hobbs said, will make students and staff adapt to reading these specific cues.

“The good news is that you already know what happiness looks like in the eyes and forehead,” Hobbs said. “It’s not as much about what we have to learn, but it’s becoming more in tune with our emotions.”

avery neal • May 7, 2021 at 8:39 AM

Amazing story!! I’m an editor at for myohsonline.com and we come to your website a lot. Love to see you guys produce so much!

Arpitha Sistla • May 7, 2021 at 9:00 PM

Wow, thank you so much for the kind words!

— Arpitha Sistla, Online Editor