Your donation will support the student journalists of Marquette High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs. You may become a PATRON by making a donation at one of these levels: White/$30, Green/$50, Blue/$100. Patron names will be published in the print newsmagazine, on the website and once per quarter on our social media accounts.

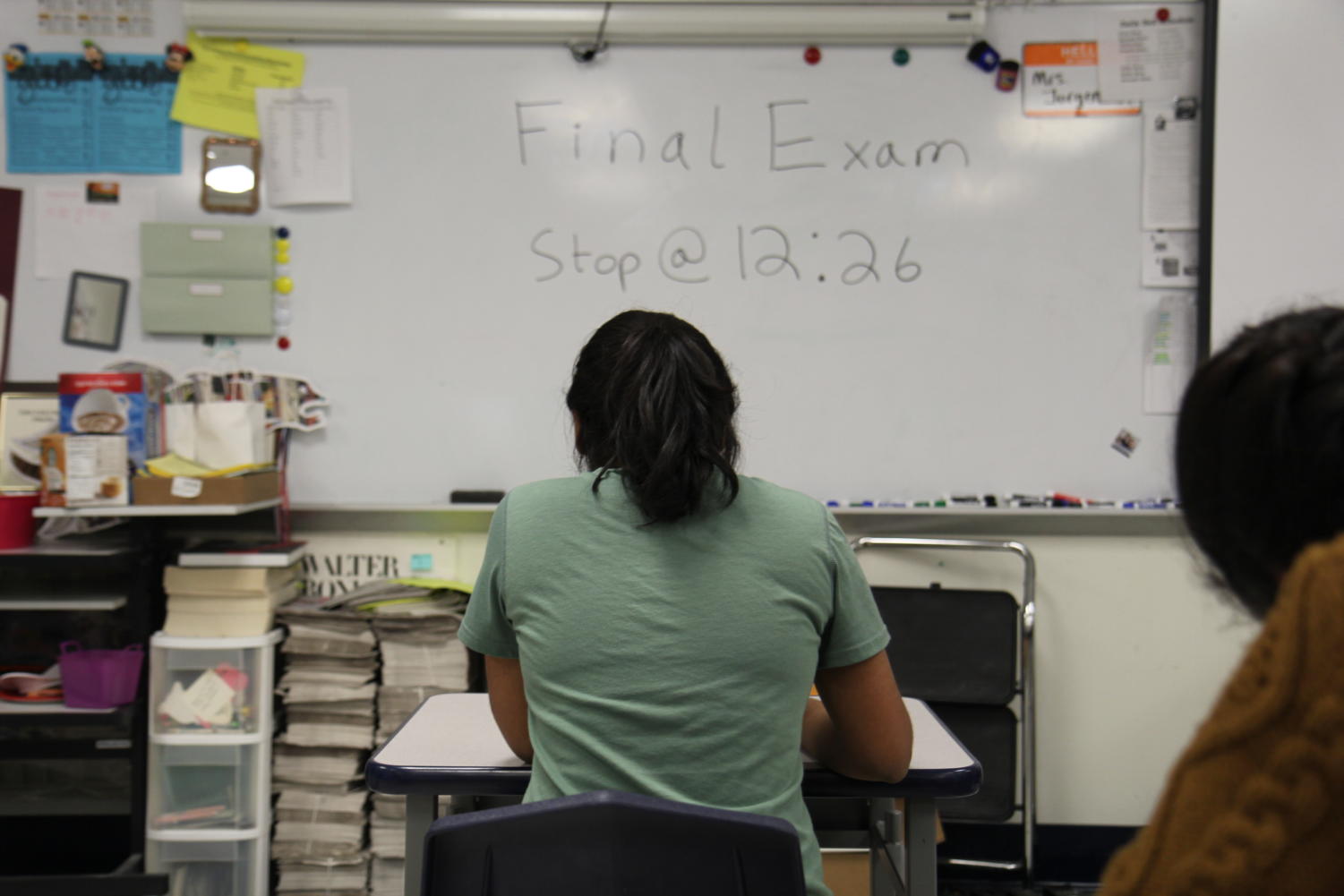

Re-Examining Finals

With the lack of a final exam policy at RSD, teachers and officials met in November to discuss their implementation and will meet in January with students.

December 20, 2017

When Leeza Kabbendjian, senior, walked through the doors of MHS for the first time as a freshman, she felt genuine excitement at the thought of tackling a new challenge.

However, differences between middle school and high school became apparent when she earned her first B in Honors Language Arts, dropping her down from an A.

“Coming from the middle school setting where grades don’t really matter, suddenly one test dropped me an entire letter grade,” Kabbendjian said. “I think that transition is unfair to put onto any individual, especially at the age of 13.”

Kabbendjian said her final reflected a momentary period of stress rather than her abilities in writing and reading.

“High school finals place this incredible weight on students, to where stress is inevitable,” Kabbendjian said. “I think we should make finals just another grade in the gradebook and not put as much weight on it.”

Beginning Decisions

A Final Exam Review Committee, made up of several teachers and district administrations, met for the first time on Thursday, Nov. 9, to discuss changing policies.

As of now, RSD’s final exam policies only address exemptions. There are no defined rules as to the comprehensive nature of the tests, the percentages attached to the exam or the makeups of each test.

Scott Szevery, social studies teacher, said the committee discussed reasons behind having final exams and gauged teachers’ opinions on the merits of finals.

“The district basically sort of realized that the final exam policy officially is very broad and vague,” Szevery said. “What we’ve been doing as teachers is following rules and guidelines that nobody’s sure where they came from.”

Szevery cautioned that any change to refine current policies will take years to truly solidify.

“Rockwood is a big bureaucracy and bureaucracies move very slow,” Szevery said. “We were just beginning the discussion, and I thought that in that sense the meeting was very productive because I think we really had a very wide-ranging discussion about what we’re trying to accomplish as educators and where do final exams fit into that set of goals.”

Szevery said that finals are meant to validate a person’s pre-final grade in the class.

“The whole idea is that if the kid is earning a B, and then they get a B on the final, that sort of proves that the final was valid and was accurate,” Szevery said.

Finals in Szevery’s classes are formatted distinctly, crafted to test a student’s depth of knowledge in the subject through a format that extends beyond the multiple-choice.

Dr. Cathy Farrar, science teacher, said the committee discussed what exactly final exams should quantify for students.

“We looked at the kind of an outcome we want from high school students in general, so like, at the end of high school, what would we expect you to take away,” Dr. Farrar said. “Then we looked at how our assessment practices are reflective of all that.”

Dr. Farrar said the talks centered around the flexibility of finals for different classes, or how they can be tailored to judge real proficiency.

“We did talk quite a bit about how, in some courses, a performance event may be better than a multiple choice and written component,” Dr. Farrar said. “Maybe in a more content-driven class, it’s more important to assess the content.”

Student Consideration

For eighth grade students at RSD middle schools, finals were weighted at 10 percent of the semester grade during the 2016-17 school year, according to the RSD website.

Issaka Thomas, freshman, found it difficult to balance the gravity of finals with the workload of multiple honors classes upon transitioning to high school.

“The difference is that I have more things to do now,” Thomas said. “I’m definitely more stressed. It’s difficult because I have a research project now as well as multiple pages of homework. I also have to prepare for tests and study for the next unit to get ready for the final.”

Though she doesn’t agree with the 20 percent weight of high school finals, Thomas isn’t in favor with the 10 percent weight either.

“I don’t like the 10 percent because since finals go over everything in the year, it’s a collective of what you learn,” Thomas said. “But, it shouldn’t be as much as 20 percent because it could greatly impact your grade if you don’t do well.”

Alex Paolicchi, senior, was a freshman when he experienced the significance of finals on overall semester grades.

In his German class, he went from an 83 percent to a 69.5 percent after scoring a 15.5 percent on his final exam. While he’s disappointed with the outcome, he owns up to the fact that it was due to his own lack of studying.

“I put C for every answer because I didn’t know any of the questions and I already knew I was going to fail,” Paolicchi said.

Despite his acceptance of this grade drop being his own fault, Paolicchi said he still thinks finals are weighted too much.

“I think 10 or 15 percent would be a better weight. I feel like they should affect your grade, but not an extreme amount,” he said.

In this instance, Paolicchi was part of the 6.3 percent of classes in which students receive at least one letter grade lower after the final is included in grade calculation, according to Glenn Hancock, director of research evaluation and assessment for RSD. Meanwhile, only 4.9 percent of classes have students that receive at least one letter grade higher after the final is included.

Deepak Manda, senior, is one of the select few to see their semester letter grade increase. Manda’s grade in his Latin class, as he approached the final, was a B.

“I worked really hard and I came in after school four days that week to learn the stuff I thought I didn’t know,” Manda said. “I took the final, did well, and it brought me up to an A.”

Manda, like Paolicchi, said that finals, generally, should not be weighted as much.

Ultimately, the weight of a final exam ought to depend on the class itself, Manda said.

“It should be based on the curriculum of the class,” Manda said. “Some classes have frequent testing and they reuse the material throughout the year. In those classes, the final should be lower because they don’t need to test overall material as much.”

Administrative Perspective

Superintendent Dr. Eric Knost recognizes the benefits of separate testing policies at the four high schools.

“I think there is some autonomy in the district,” Dr. Knost said. “It’s up to the individual classes as far as what to collectively test students on based on what individual departments decide.”

The strict use of specific policies, however, may not be completely functional in school settings when it comes to final exams, Dr. Knost said.

“I think schools nowadays have been forced through governance and laws to perform like bureaucracies and I don’t necessarily think that’s a good thing because it hinders creativity,” Dr. Knost said. “Creativity needs to be alive and well in our schools.”

Dr. Knost said he believes in establishing a free-form testing policy, one that is open to changes in format within each individual class.

“I’m not a superintendent or educator that believes in more standardization,” Dr. Knost said. “I’m not a proponent for standardized testing and I’m not a proponent for every teacher doing the same thing. We need to make sure that we have some equitable measures of how testing is handled in each individual classroom.”

Dr. Shelley Willott, executive director of learning and support services at RSD, said that despite not being written into policy, some rules regarding final exams are standard.

“The 20 percent weight was determined years ago, but it is not specifically written into district policy,” Willott said. “The district policy just states that we must give exams.”

But Willott is also in favor of developing variable testing policies so teachers can proctor finals conducive to their particular class types.

“Weighting finals differently will most likely come up in the conversation as we examine best practices in assessment and make decisions,” Willott said.

Dr. Takako Nomi, assistant professor in educational studies at St. Louis University School of Education, deems final exams as a necessity to determine students’ college-readiness, albeit with some expectations.

“As a teacher, you have to prepare students to do well on exams, but those exams may not always be reflective of a student’s comprehension and understanding of the material,” Dr. Nomi said.

“You would hope that the teacher has multiple ways to ensure that the students understand the material, like multiple-choice questions, essays and more.”

Dr. Nomi said the format of final assessments should be based on the subject tested as not all subjects can be tested for mastery through identical methods.

“Teachers should have some grasp on where students are throughout the course and not simply rely on the end-of-course multiple choice assessments,” she said. “In general, students should be tested through other forms of testing.”

Student performance on assessments and final exams also may be influenced significantly by testing anxiety, thus unexpectedly dropping student grades, Dr. Nomi said.

“I would imagine some students have anxiety,” she said. “Discussions, homework, presentations, projects, for example, should also help assess.”

In regards to final exemptions, a policy seldom offered in college, Dr. Nomi said dropping a class’s exam may have some merits.

“In college, depending on the instructor, some student have the option of dropping the lowest grade,” Dr. Nomi said. “Exemptions depend on the overall future purpose of students. If you have too many exams, you should be allowed to drop a final that is not critical to your goals.”

Principal Dr. Greg Mathison finds it necessary to give teachers more autonomy over their final exams to ensure properly-formatted assessments per subject.

“Sometimes we’re making finals because we have to have a final at 20 percent, and maybe 20 percent might not be the number. Maybe 10 percent would make sense for this class,” Dr. Mathison said. “But in another class, maybe it’s cumulative and I need to see everything that the kids have learned from that year or that semester, and it needs to be 20 percent. Maybe it needs to be more.”

Teachers’ Viewpoints

For math teachers, the current weight of finals seems fitting: a 20 percent justifying a semester’s worth of education.

“In math now, the final is very effective,” Matthew Nienhaus, math teacher, said. “It’s very predictable of what you would deal with in college. Our goal is to not only assess whether or not what we’ve done in class but also to help teach you to deal with a high-stake assignment like that.”

In the math department, the general consensus agrees with the 20 percent weight, Nienhaus said.

Though the current weight of finals has not faced resistance from other departments, Sophomore Principal Richard Regina said it is important to realize that a generic scantron-based final may not work in all contexts.

Similarly-formatted language arts finals, for example, are not entirely representative of a student’s understanding of the subject, Regina added.

“What a final exam looks like in math certainly might be a lot more different than what a final exam looks like in language arts or in PE,” Regina said.

Regina said his past experiences as a language arts teacher at MHS pushed him in favor of eliminating the uniformity of finals in all classes.

“In my 14 years of language arts, I felt like our final exams evolved into something we thought was really applicable and useful,” Regina said. “As I became a much more seasoned teacher, I really got some good class discussions going, which is much more applicable for life.”